Future Ruins and New Worlds

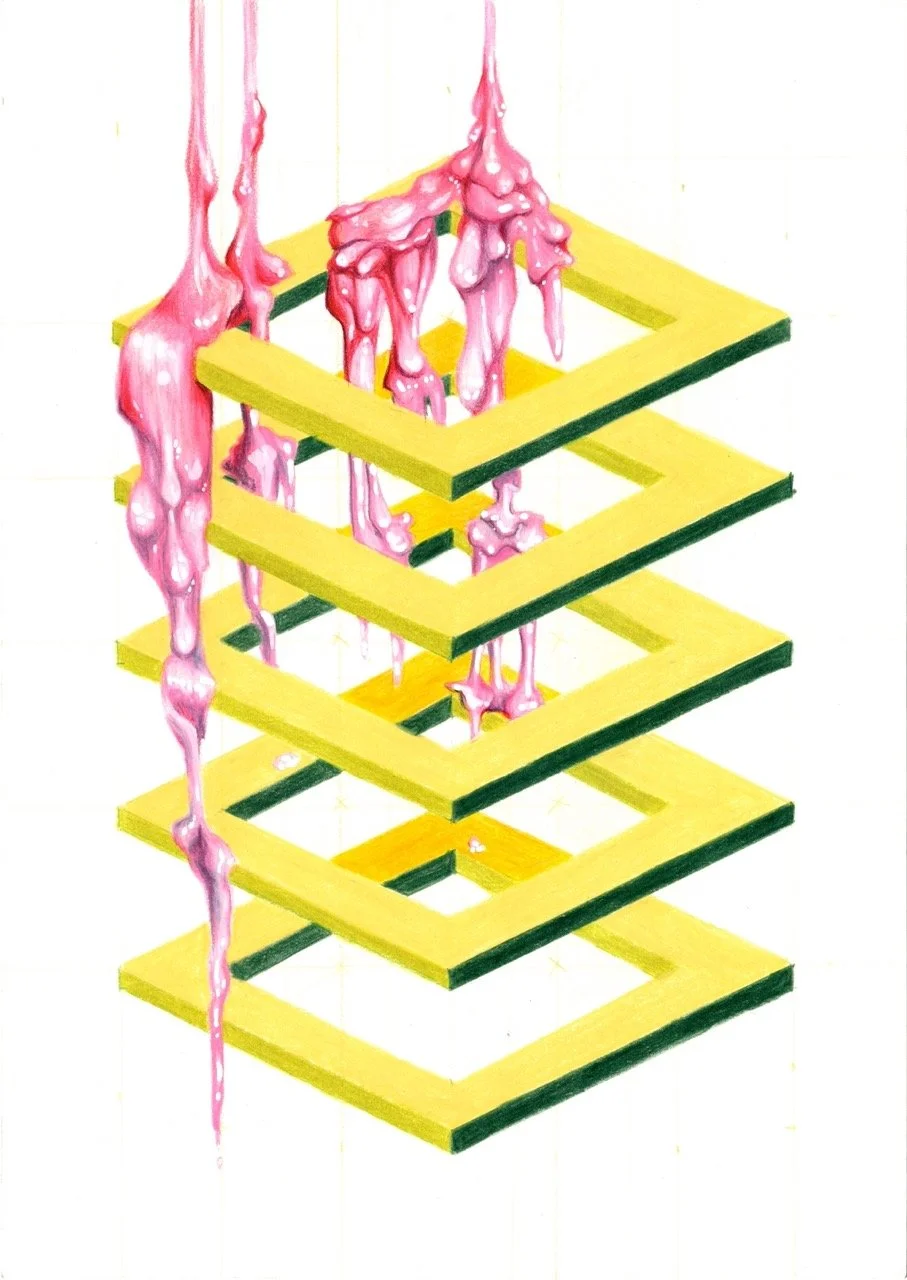

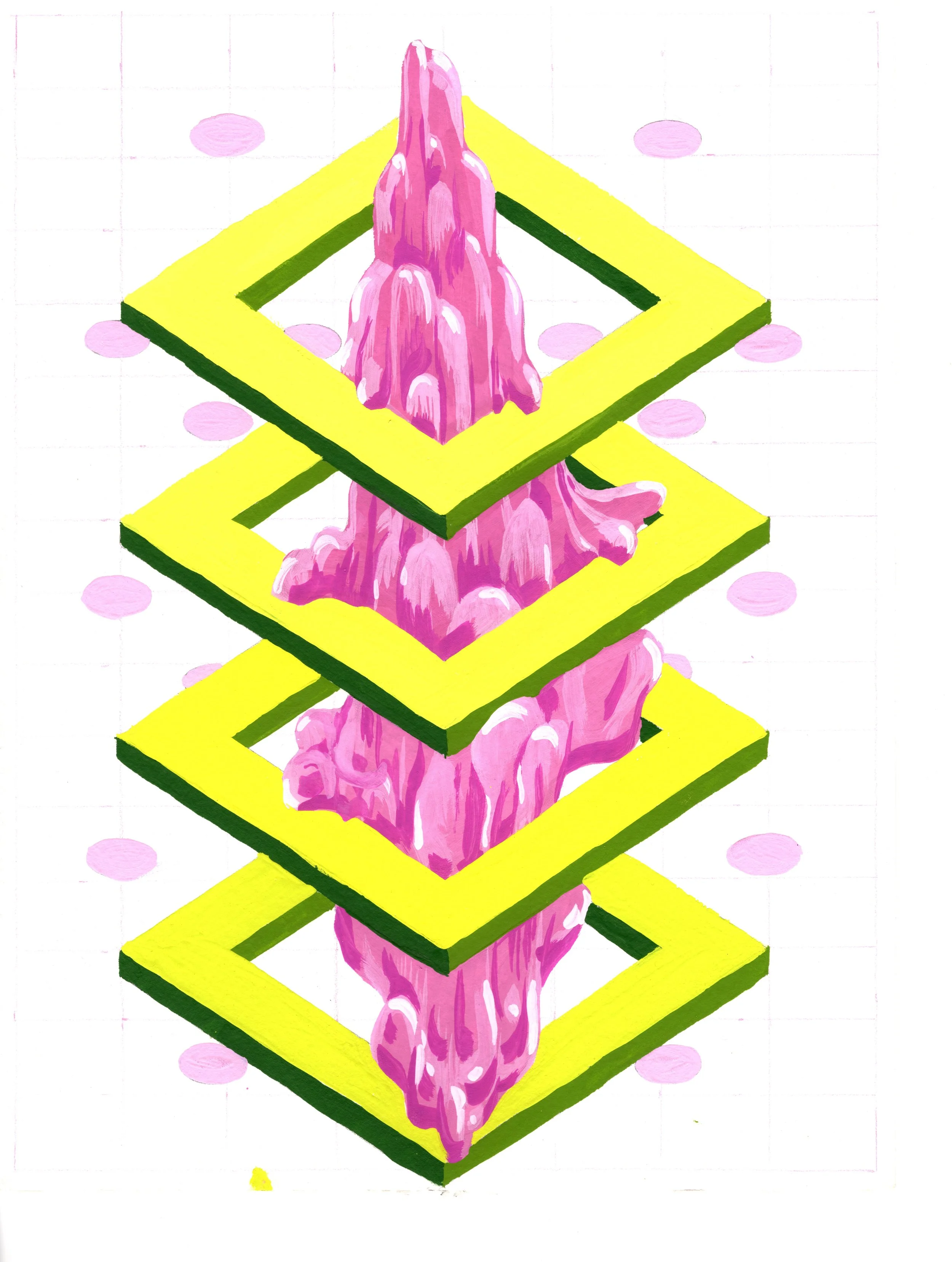

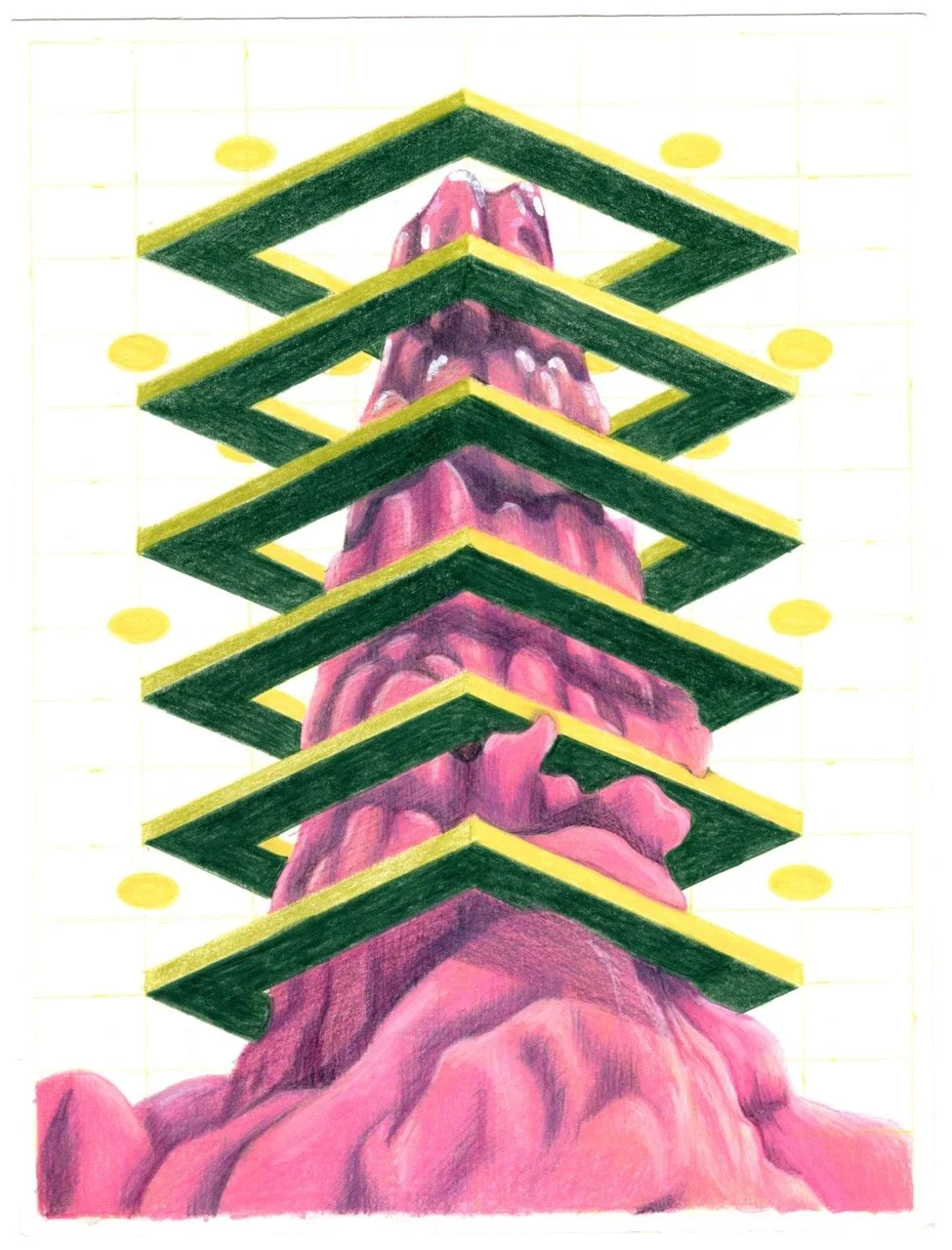

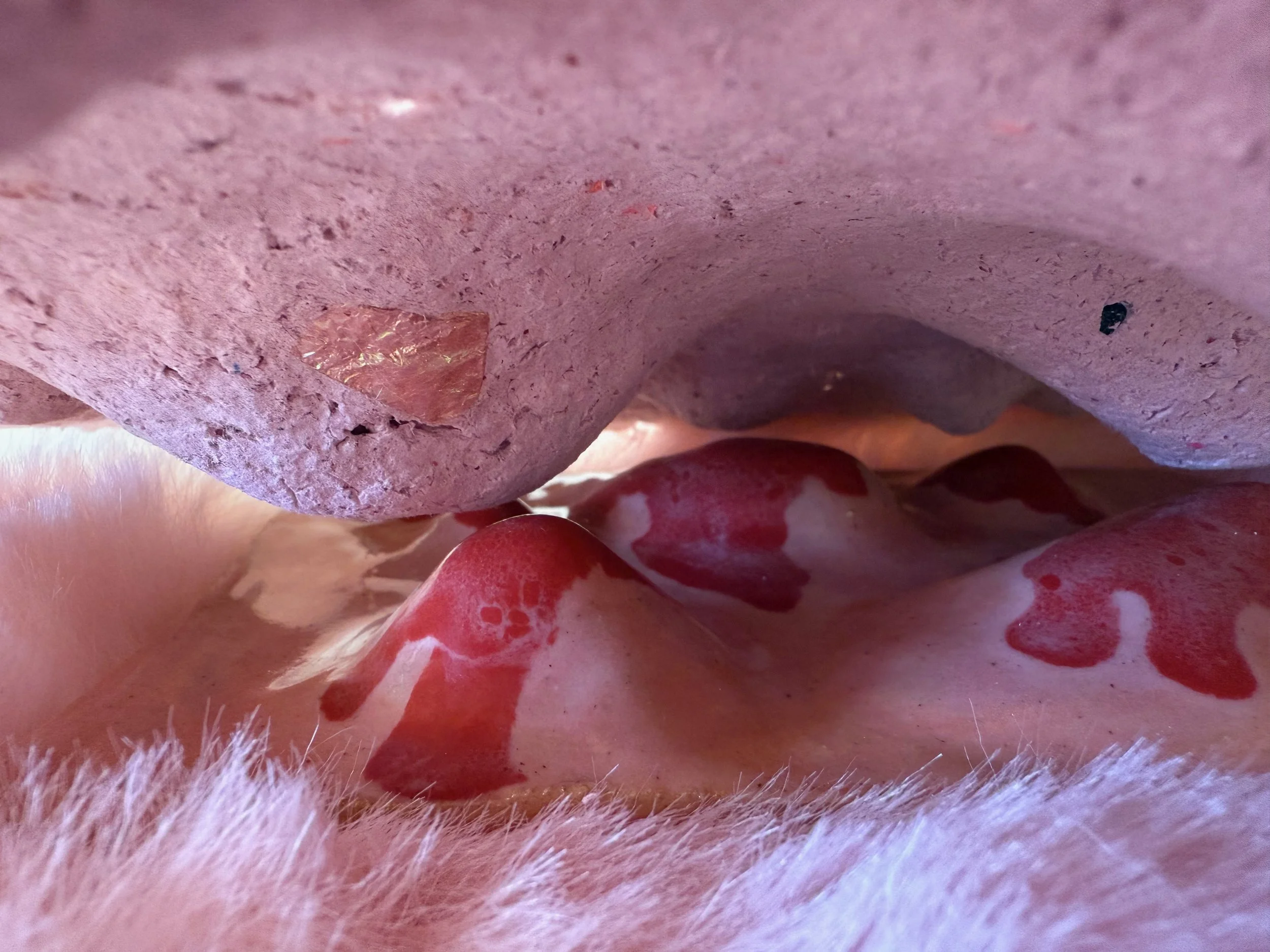

Future Ruins and New Worlds is a series of works in progress. Initiated as part of a collaboration with Dr. David Watkins, this series consists of gouache paint studies, short films, pencil drawings, ceramic objects, recycled paper-casts and a research paper.

FRNW explores imagined internal and external worlds, embodied and glitched worlds, and seeks to take the conditions of the world we are in now, exactly as is stands, to build these new imagined worlds on to.

Research

Embodying Worlds

Dr. Ruth Jones

Creativity is at the heart of any new world we seek to build. ~ Lola Olufemi*

Building worlds is an imaginative enterprise. Those who get to imagine the world otherwise can impact the worlds that are built and the world we navigate now.

But, to imagine an idealised world, totally separate and unbeholden to the one that is here, is unrealistic and exclusionary. We cannot build new worlds in a vacuum, with ideal conditions and resources, in isolation. The notion that we can is inherently patriarchal, colonial and capitalist.

We come close to this ideal null state from which to start afresh in the theoretical, academic spaces that hubristically delineate and label specialisms and expertise; that design experiments with control groups - as if ‘controlled’ is the natural state of matter. And we find it, too, in the white cube of the gallery space. These pinnacles of Western, classist and colonial authority; these white cubes and hallowed halls deny the messy realities of our entangled world. They refuse to acknowledge decoration, colour, or other cultural signifiers that speak to anything other than the continuity of whiteness. They disguise the labour, maintenance and resources required to maintain the illusion of an institution impervious to time and decay. This is the situation in which we as contemporary artists and researchers find ourselves; we operate in this null space, weaving new worlds out of the materials and contexts of our existing one before isolating them in the nebulous non-reality of the gallery and the peer-reviewed paper.

McKenzie Wark warns of our reliance on the subdivided categories and expert scholars in the introduction to Sensoria: Thinkers for the Twenty-First Century, 2020. It seems that our research should undertake ‘the common task of knowing the world’,[i] but nobody can know the totality of, well, anything. Knowing worlds (and through extrapolation we can posit this extends to how we think about building them too) is never completely achievable. And then of course there is the question of who this ‘we’ is that undertakes this task? The reality of the world we currently live in is one of inequality, disparity and violence. Those on the receiving end of such violence, disparity and inequity are seldom invited into rarefied spaces like academia or the white cube. Gaining access to these institutions is fraught with racial, classed and gendered barriers.

This essay, with the questions it poses, theories it considers and positions it argues, is not a panacea. Instead, it traces a fragmented and biased investigation of world-building through bodies, embodiment, art, and feminist interjections.

~

Undertaking the project of world building, of imagining otherwise, is not often a task assumed by the majority. And worlds, once made, need looking after. Care and maintenance are thankless duties as they currently stand. Value systems are called into question when we imagine building worlds; the making is all very well, but the tidying up? No thanks. Feminist scholars have fought hard to have care seen as work. You can tell that its work because no one wants to do it. It isn’t the glamourous bit, but without it, everything falls apart. And what’s more, how our society has valued care says a lot about who is at the front of the line in the world-building queue. According to Joan Tronto, care makes visible the power structures and value systems in our society.[ii] But what is less visible is what is at stake: that the receipt of care gives us the chance to exist beyond the paradigm of a body performing a function, and instead lead what Emma Dowling identifies as a meaningful life.[iii]

As Lola Olufemi argues in Feminism Interrupted, women’s bodies carry the demands of capital, in the myriad ways they are classed, racialised and gendered, leaving little time or energy for creative endeavours of any kind[iv]. Our bodies, under capital, are determined to have uses, and those whose bodies carry a uterus are assigned the role of social reproduction. But bodies should not be prisons when they contain worlds. Legacy Russell encourages us to think about our bodies as journey’s rather than fixed destinations.[v] Gendered bodies carry functions and assumptions.[vi] But as Russell says, body is a “world-building word, filled with potential, and…filled with movement.”[vii] She sees the potential of refusing to fix our bodies in gendered functions, instead suggesting we glitch, refuse and disobey.[viii]

In our bodies we find worlds of labour and care, and hopefully meaning. But how can we determine what is meaningful for us? Through embodiment? Long have women been detached from their bodies, under capital, patriarchy and coloniality. The project of the enlightenment was to create a hierarchy of knowledge, with embodied and experiential knowledge routinely place at the bottom. But that was borrowed from the ancient Greeks, who determined that women were a different race from men, and as Anne Carson discusses in The Gender of Sound, this was most apparent through speech and sound. [ix] So troubling was the voice of women because they lacked sophrosyne (self-control)[x] that they believed that women used speech only to express their internal emotional state, without logic or reason.[xi] Embodied knowledge, perhaps? Emotional intelligence, maybe? The ancient view of women is, as Carson says, “…the creature who puts the inside on the outside. By projections and leakages of all kinds – somatic, vocal, emotional, sexual – females expose or expand what should be kept in.”[xii] Sounds messy. We still feel the impact of these classical arguments even now, especially in the (d)Deaf community. Learning to lipread rather than to sign was encouraged because sign language was believed to be pernicious. Carson reminds us that sign language is a direct presentation of what is happening on the inside made visible on the outside, and thus lacking logic and self-control.[xiii]

Feminist scholars bring alternative insights, ones that don’t decry an internal sense of knowledge. Luce Irigary tells us that men think through the logic of sight, primarily because they see their genitalia, but women don’t have to see theirs to know it is there.[xiv] A different state of embodied knowledge. Of course, this can be read as essentialist in its argument, and it is important to remember what Russell has told us, that we should glitch and shift away from gendered functions. But there are some worthwhile things to think about, and be claimed if they resonate. As Irigary rather poetically declares:

Our all cannot be projected, or mastered. Our whole body is moved. No surface holds. No figure, line, or point remains. No ground subsists. But no abyss, either. Depth, for us, is not a chasm. Without a solid crust, there is no precipice. Our depth is the thickness of our body, our all touching itself. Where top and bottom, inside and outside, in front and behind, above and below are not separated, remote, out of touch. Our all intermingled. Without breaks or gaps.[xv]

Our bodies, our worlds, no surface holds. This embodied knowledge, raw and emotional, leaking out, communicative, can help us determine what is meaningful to us. Audre Lorde calls this the erotic, the in-between space from our sense of self through to our most chaotic feelings that helps us determine our own internal sense of satisfaction.[xvi] Once again, we see how our embodied sensations, our power and our own knowledge have been divested from us:

As women, we have come to distrust that power which rises from our deepest and non-rational knowledge. We have been warned against it all our lives by the male world, which values this depth of feeling enough to keep women around in order to exercise it in the services of men.[xvii]

Determining meaningfulness, then, can be an embodied understanding, if we can learn to trust it.

This leaky, embodied knowledge, emotionally connecting our insides to our outsides doesn’t need to be curtailed, isolated and parsed through an intellectual filter, logically considered and isolated from its context. It enriches our understanding of our place within the world, embracing the impossibility of disentangling our senses and emotions from our messy reality. We are better positioned to take the existing world as it is and build on to what is already there.

And meaningfulness and creativity are central to imagining how to build a world, and more importantly, how to care for a world once it’s built. Those who care in this world are well placed to establish the conditions under which new ones could be imagined and built, but they also shouldn’t have to care based on the racialisation, social classing or gendering of their bodies. Caring is important, but those who perform the acts of care are seldom cared for or about by society. Olufemi’s assertions echo back again; “Without the demands placed on our body by capital, by gender and by race – we could be freed up to read, write and to create.”[xviii]

Creativity and the sites for its production are seldom held in common. The white cube gallery, divorced from reality as the place where creativity is held in suspension for consumption of the most privileged is not what inspires the creation of artforms. Strangely, though, gallery spaces are part of our commons, at least in the UK.

In his conception of aesthetics, Jacques Rancière points to the politics of constituting public or common spaces; who is permitted to occupy them and how they are permitted to imagine them. He uses a Platonian example which refuses to acknowledge workers as political beings, stating that they have time for nothing but their work and so never attend the people’s assembly.[xix] Rancière discusses this as a classed exclusion from political representation or rights: “Their [workers] ‘absence of time’ is actually a naturalised prohibition written into the very forms of sensory experience.”[xx] This naturalised prohibition draws parallels to the moral responsibility of caring that is considered a naturalised characteristic of those with uteruses. The act of caring exerts limits upon the time women have to be present, but it also redacts them from public space. Even when spaces are held in common, the demands placed on us by capital mean those spaces are not free to be occupied, effectively eliminating us from sensory experiences.

Sensory experiences, such as access to art in common spaces, allow us the opportunity to play, imaginatively. Play is freedom from our assigned roles in contrast to the limitations placed on our bodies and minds by work.[xxi] Play, then, much like care, gives us the chance to live meaningful lives outside of the constrains of capital. Art provides us sensory experiences with which to play, giving us the chance to imagine otherwise and to determine our own internal sense of meaningfulness. Building new worlds that make the space for us to play, care and be cared for should be a priority.

Weaving these understandings of play and care into the sensory experiences available within art, in these ‘common’ spaces is all very well, but we also need to be able to ‘read’ the artworks. McKenzie Wark suggests our attentional skills need work. But, should we require a snapshot to help us with our attention we can: “…Attend to the in-between spaces. Avoid the binaries. Observe the connections. And act on them.”[xxii] Reading the sensory experience of art, playing with it intellectually and emotionally, helps us to find the worlds contained within it, and closely consider how we might build our own. Art can contain multiple meanings for those viewing it, but as a passive object, Rancière tells us it cannot contain those meanings in and of itself.[xxiii] That art is capable of maintaining these contradictions as a passive container activated only by its viewers, is important. In this sense, art can act as a catalyst. Rancière cautions us that a reading, an understanding and experience of the aesthetic, sensory artwork is not interchangeable with an understanding of political conditions that lead to emancipation. We won’t suddenly be free from our material and bodily conditions just by looking at an ‘art’.[xxiv]

But let’s attend to some of Wark’s in-between spaces. Let’s think and speak through the body and with the body, as a journey, and the representation of an interiority that no surface holds[xxv], as those who put the inside on the outside[xxvi], to imagine new worlds. Speaking new worlds into being, claiming the spaces that we have been excluded from, we can see why our voices were decried. Carson enumerates the ancient and modern belief that ‘madness and witchery [and] bestiality’ are commonly associated with women’s voices, and of course the ‘seductive’ power of women’s voices, such as that owned by Aphrodite.[xxvii] That magic, or witchery, as seductive as it is, suggests a power the re-imagines the world as it is into something new, unknown and unspeakable. We “discharge unspeakable things…say what should not be said.”[xxviii] This seductive power is in part held by bodies that own two mouths[xxix]. Reduction to bodily functions, which, taking Russell and Iriagary’s advice we resist and glitch, suggests a power within those functions. Seductive speech patterns, bestial conditions, and witchery all suggest a form of mesmerism feared by the hierarchical institutions of colonial, patriarchal, white authority.

Mesmerism, a contested pseudo-science from the 1780s that looked at bodily forms of communication and power, is a curious historical glitch. ‘Invented’ by Anton Mesmer, it has since been reclaimed as a nebulous and uncanny verb, suggesting magic, intrigue and manipulation. A sort of in-between-ness that is embodied in the voice, neither science nor magic, fact nor fiction. Those who hold this mesmeric power can transport their audience to alternative planes of feeling.[xxx] Jane Goodall suggests they can “…create a sense of expanded destiny and heightened meaning…to all who wish to embrace it.”[xxxi] There is a sense of dis-ease in being transported by the power of someone else, being pulled into their imagining of the world, heightening the meaningfulness of their imagination. Their own sense of internalised satisfaction[xxxii], perhaps.

New worlds of mesmerism are forming in the digital commons, equally discredited as pseudo-science. ASMR or Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response, refers to the pleasant tingling sensation across the scalp, neck and shoulders that some people feel upon listening to certain repetitive sounds, whispering or watching repetitive visual stimuli. Defined by its audience rather than through rigorous, academic or scientific discourse, this in-between phenomenon, mesmeric in quality, affects the mental and physical state of its recipients. Inaccurately described sensory experiences[xxxiii] are the direct result of nuanced performances of care, captured digitally, and repetitively consumed. Women monetising their performance of emotional labour through likes and shares. Perhaps that’s why mesmerism and ASMR are discredited, predominantly belonging as they do to women. Silencing the voices of women, through whichever mouth they speak, is, after all, one of the principle projects of the institution of patriarchy.[xxxiv]

~

Inconclusively we discover that rather than a destination met, this partial examination of knowing, describing, feeling and being in the world and being in a body gendered by society, has led us on tangent after tangent. Such is the nature of living in a world and in a body that is intertwined, inexorably, with everything else. Isolating our worlds and ideas can provide us with a sense of (misguided) mastery. Our creative and care-ful endeavours return us to our bodies to discover internal satisfaction and meaning. We read and know fragments of the world, connecting ourselves through our sensory experiences to our imaginations and back again. And we glitch away from the assigned functions of our bodies in order to claim the opportunity to build new worlds. Much of this is contradictory. But as Donna Haraway says, we hold onto our contradictions because both or all are necessary.[xxxv] And now, this short, entangled study, selected as research, presented as art, read as a partial world - lives in you, the reader. You get to imagine the world otherwise. You get to impact the worlds that are built. You will impact the world we navigate now.

Notes

*Lola Olufemi, Feminism, Interrupted: Disrupting Power (Outspoken) (London, UK: Pluto Press, 2020) p84

[i] McKenzie Wark, Sensoria: Thinkers for the Twenty-First Century (London: Verso, 2020). P 2

[ii] Joan C. Tronto, Moral Boundaries: A Political Argument for an Ethic of Care (New York: Routledge, 1993). P 180

[iii] Emma Dowling, The Care Crisis: What Caused It and How Can We End It?, First edition paperback (London ; New York: Verso, 2021). P 45

[iv] Lola Olufemi, Feminism, Interrupted: Disrupting Power (Outspoken) (London, UK: Pluto Press, 2020). P 146

[v] Legacy Russell, Glitch Feminism: A Manifesto (London ; New York: Verso, 2020). P146

[vi] Russell. P 41

[vii] Russell. P 8

[viii] Anne Carson, The Gender of Sound (Silver Press, 2025). P21

[ix] Carson, 1995, p11

[x] Carson, 1995, p14

[xi] Ibid, p15

[xii] Ibid, p19

[xiii] Carson, 1995, p20

[xiv] Luce Irigaray, This Sex Which Is Not One (Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press, 1985). Pp 25-26

[xv] Irigaray, 1985 p213

[xvi] Audre Lorde, Your Silence Will Not Protect You (UK: Silver Press, 2017). P23

[xvii] Lorde, 2017 p23

[xviii] Olufemi, 2020 p84

[xix] Jacques Rancière, Aesthetics and Its Discontents, English ed. (with minor revisions) (Cambridge, UK ; Malden, MA: Polity Press, 2009). P24

[xx] Rancière, 2009, p24

[xxi] Rancière, 2004, p31

[xxii] McKenzie Wark, Sensoria, 2020, p 71

[xxiii] Rancière, 2009 p33

[xxiv] Rancière, 2009 p33

[xxv] Irigaray, 1985 p213

[xxvi] Carson, 1995, p14

[xxvii] Carson, 1995, p4

[xxviii] Carson, 1995, p26

[xxix] Carson, 1995, p23

[xxx] Goodall, 2008, p87

[xxxi] Jane R. Goodall, Stage Presence (London ; New York: Routledge, 2008). P 8

[xxxii] Lorde, 2017 p23

[xxxiii] Efe C. Niven and Sophie K. Scott, ‘Careful Whispers: When Sounds Feel like a Touch’, Trends in Cognitive Sciences 25, no. 8 (August 2021): 645–47, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tics.2021.05.006.

[xxxiv] Carson, 1995, p5

[xxxv] Donna Jeanne Haraway, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, Reprinted (London: Free Association Books, 1998). P149